As the end of my MA approaches, it’s time to sum up my use of this blog for the Methods & Processes module.

The initial purpose of die unendliche werkschau was to document my work as it went, providing me an instrument to reflect my practice and its evolution with. I had done this before and I had always found it useful to write about my work and document its intermediate stages, so at first I saw it as a good way of resuming a good habit I had lost. As a matter of fact, however, the time pressure that I’ve found myself in, due to reasons entirely external to my academic commitment, has meant that more often than not I have prioritised pushing my work as far as I could over documenting it. Not only hasn’t my design process really enjoyed the benefits of an ongoing documentation (most of the posts documenting my work were written after the projects had been concluded), but also there hasn’t been a specific focus dedicated to the methods or processes I used in my work. As it stands, this blog is an assemblage of recollections and fragments from different projects I have worked on in and outside the MACP whose connecting thread is very thin at best.

Because I can’t really ask my tutors to sift through all of the entries looking for the bits relevant to it, I have decided to write this post summing up the M&P aspect in the previous ones and recollecting other parts of my design process that haven’t been mentioned on this blog so far.

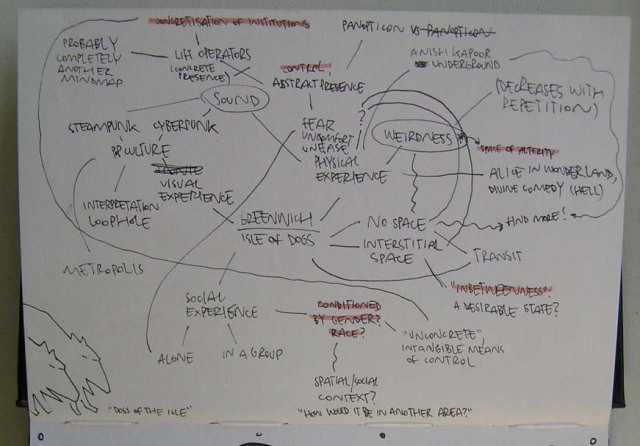

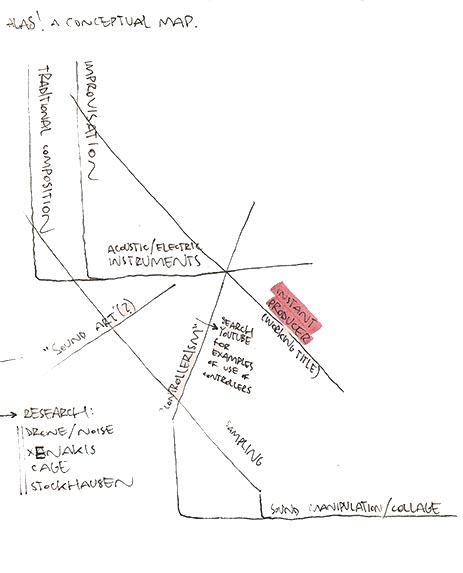

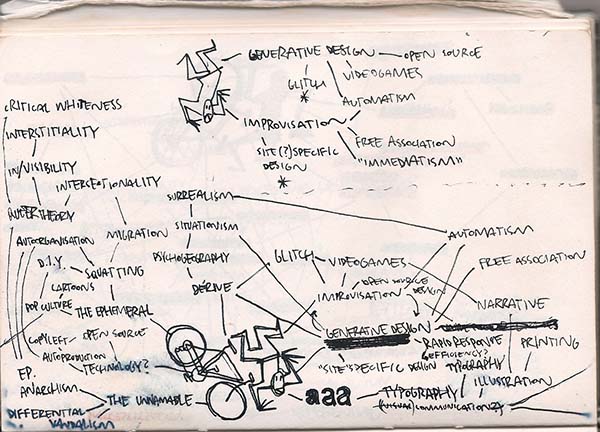

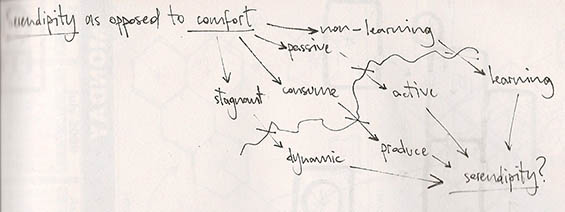

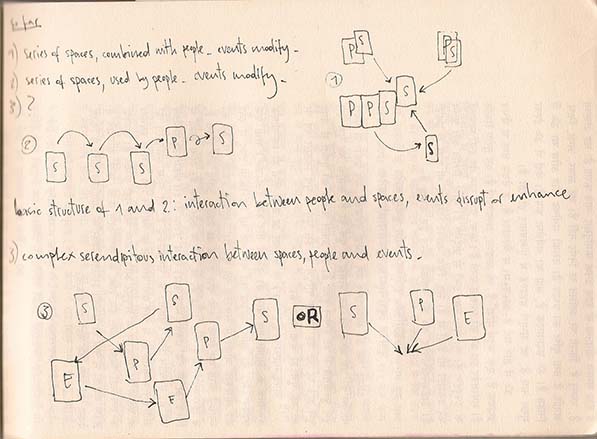

The single most important tool that I have used throughout the MA was the diagram. Laying out words and objects on paper and drawing up connections between them has been very useful not only to help me understand the context I was operating in, but also to expand and further my work by providing an overview of its taxonomy and its tendencies.

Whilst developing my major project, for instance, I devised two diagrams to roughly describe the mechanics of the two games I had already sketched out. By defining the common elements in the first two games, this provided me with a sort of a visual lexicon to draw diagrams for the third one, prior to having any concrete idea of how it was going to be structured. In this sense, the diagram wasn’t just a representation or taxonomy of what I was doing, but an active tool in the creative process.

Likewise, in my work on the Networks in Crisis brief, I summarised my first presentation in a diagram in which my subsequent project found its basis. Working on the visual representation of the arguments that had informed my early research on the structure of the Internet helped me identify the directions that were open for my work to take at that stage. (The diagram that I’m referring to can be viewed as a .pdf here.) I was ultimately able to transcend these options thanks to the clarity that this representation brought into my sprawling research, which indicated that I was venturing more and more into a field of which I only had a vague understanding. Hence the choice of remaining within my set of practical design skills instead of pushing my work beyond a boundary that I had never even perceived as such.

Other than this, the TAZ project on the Greenwich Foot Tunnel was perhaps the one in which the greatest variety of methods was deployed.

One of the first things I did in that project was to visit the archive of the Greenwich Heritage Centre, an approach that, in retrospect, was obviously indebted to my years at the Faculty of Architecture in Rome, in which it was always considered of paramount importance to place things in their historical context. I would go to the extend of saying that, except for a couple of minor findings that were hardly relevant for any of my interests in the Tunnel, my trip to the archive was an utter waste of time: in this sense, it was the latest and maybe final step in my long trajectory of withdrawal from the bases of my university education.

A series of field trips would yield much more interesting results, as I proceeded to observe and document both the physical characteristics of the Tunnel’s space and the dynamics that it facilitated in the public. The latter could be reconstructed mainly through traces left in the Tunnel – cigarette butts, graffiti, litter – and without knowing about it yet, I was drawing a map of the environmental behaviour in that space.

Much of my subsequent work came from the observation of the apparent contradiction between the overstated prohibitions of potentially safety-threatening activities in the Tunnel and the carelessness that seemed to be attested by these traces.

When I decided to focus on this incongruity, and specifically on the overwhelmingly present prohibition signs that were maybe its only designed manifestation, I tried the approach of what I’ve called detypefacing: undermining the authority of the prohibitions by redesigning the signs with typefaces different than their original.

If this was exploring the relationship between authoritativeness and a perceived neutrality of the visual language and typography, it was still something of a one-liner and a typographer’s joke, and I didn’t pursue it any further.

The tool that would achieve the final (?) deconstruction of the prohibition sign was a little device that a friend suggested I market as a smart phone app under the title of “iDon’t” (and can be viewed here): a Flash application in which halves of existing road signs could be randomly combined into a number of pure decontextualised prohibitions, visually credible and coherent symbols that signify nothing but themselves. The series of signs that constituted the project’s outcome was entirely devised through this self-made combinatory tool.

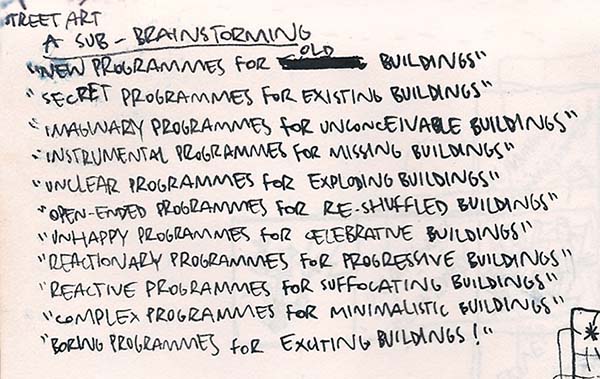

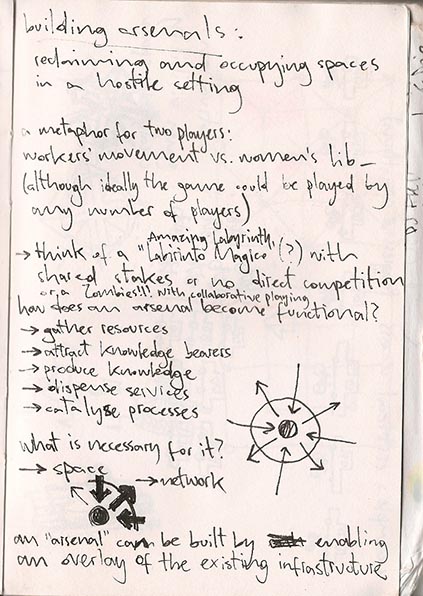

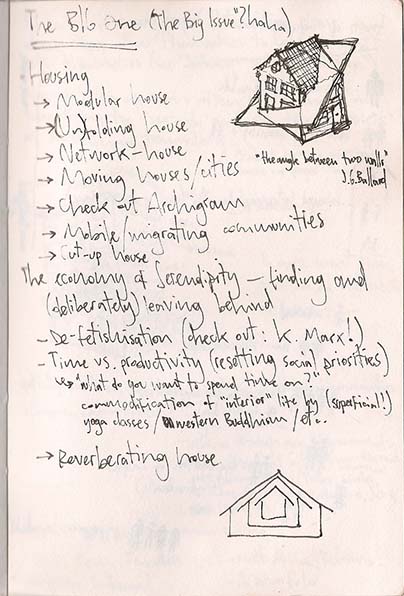

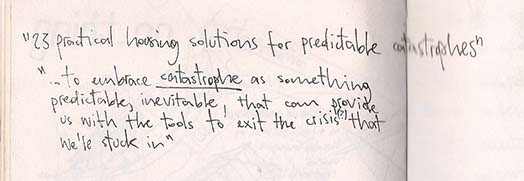

Writing has been another important way of progressing with my work, both to explain it to other people and as an aid in the creative process. The assignments of writing out a brief and a context report for the major project set a neat timeline for its development, encouraging me to round off each of its stages by fixing them in self-contained texts. Similarly, taking part in the Seeding Futures symposium and giving a presentation of an intermediate stage of my work was another opportunity to solidify it in a form that, despite being unfinished, was recognisable in its features and ultimately heading in a clear direction. Other than this, my sketchbooks abound in notes, slogans, quotes both real and invented, unorderly lists of objects or concepts, fragments of imaginary papers, explanations of one or another particular aspect of my work.

Writing is to me more than drawing a quick way to give a tangible form to concepts and ideas, allowing me to interact with them in a space outside of my head. In this sense, it is ironic that I wasn’t able to update this blog regularly, because I thoroughly recognise how much it would have benefitted my work.

Both writing reports about the design process and presenting it to an audience could be subsumed under the idea of precipitating the design process into a unique and intelligible form. Interestingly, this could be a more general description of design practice in its entirety – cf. Tony Fry’s notion of design as “not (…) bringing something into existence (which it does incidentally) but rather, the giving of direction via its efficacy” (Fry, “Homelessness: a philosophical architecture” in Design Philosophy Papers, Issue 3, 2005) – but as a mechanism it can be applied to different stages of the design process, thus recontextualising what we normally understand as a designed product as one of the many outcomes that a design process can yield.

Finally, prototyping and testing a project is a practice that can hardly be avoided in design work, and which I have approached with a certain critical caution. The following considerations are mainly based on diffuse tendencies that I have observed among my course colleagues, and they partially apply to the use of cultural probes – a method that I have, however, never worked with myself.

When setting up an encounter between an unfinished work and a potential user, it is easy to fall to two common and divergent temptations: reading the tester as an absolute other who is entirely alien to all parts of the design process, and elevating the tester to an absolutely representative and relevant sample of the project’s audience. In the first case, the designer will typically fail to take notice of the users’ previous knowledge, experience and opinions regarding the test’s subject matter, preparing a closed framework in which the tester’s agency is comparable to that of someone who answers questions on a multiple choice test; in the second one the test might leave more space to the users’ responses, but the very choice of the testing persons may already imply a bias of some sort towards the prototype and/or its author. Both mistakes are, to a certain extent, intrinsic to the practice of testing, and it may not be worth the effort of investing time and energy into avoiding them in the framework of an academic project. In my opinion, it is instead important to be able to read the results of a testing in relation to their context, and to acknowledge their inherent arbitrariness, rather than seeking some sort of legitimation from the mystifying practice of generalising the outcome of a very limited and located experiment. The use of prototyping and testing in my projects has been intentionally directed as a heuristic tool more than to measure any set of absolute values such as viability or usability could be. It is for this reason that I have been myself one of the testers of every prototype I have created so far, and that I heavily intervened into all of the other tests, trying to gather qualitatively relevant information by steering the tests into the directions that I found most promising while they were happening, instead of simulating a scientific neutrality towards my work.

Within the MACP, my projects that most relied on testing in their development phase were the last two, Discordian Chess and Home Sweet Home, for the obvious reason that they both aimed to be engaging and enjoyable games. In the former, I have played a series of chess matches against myself, testing different sets of slightly modified rules, and I have documented them with animations reconstructing the course of each match, which can be viewed here, here, here and here. In the latter, I have managed to gather a number of friends and relatives in a few occasions to play different stages of development of the three card games I was working on. More than focusing on the feedback that I got, which was mostly based on a shallow insight of my work whilst being positively skewed by the personal relations I had to the testers, I used these occasions to verify the working of the game mechanics, individuate loopholes in the rules and proof the quantitative relations between the different types of cards. These tests were poorly documented due to my great involvement in coordinating the other testers whilst taking part in the test myself and engaging with the different behaviours that would arise around the table. The observations borne out of them, however, were crucial for the completion of my project.

Thank you for reading through all of this :-)